Maelstrom #1

Reflections of a very ordinary bloke 'On Death'.

On Death

‘The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living’, Damien Hirst (photo: Getty Images)

Death is present

Human finitude which we term mortality by which, of course, we mean death.

Close your eyes, picture it now, your death. Go on! You can’t can you?

The yawning dread of our own non-existence. Oblivion. No trace. Nada. Nothing. The final full stop. Game over. We’re born, we make some noise, we die. The fact I will one day cease to exist is an irrefutable truth.

Today, if we don’t like a nasty niff we deodorise it or light a scented candle or clean the offending item.

Death holds a fascination over us. We often infantilise it, but it’s horrible, horrendous, horrifying even. Each day edges us that little bit closer, like those ‘Penny Falls’ coin slot machines in amusement arcades. Death doesn’t so much knock for us as sit in a side room, hands folded, waiting.

In the past, there seemed much more of it, a pressing companion along life’s passage. Today a Facebook anniversary memorialises moments in our lives, snapshots of us less decayed but no less dying. ‘Cheer up, you miserable tit!’, you may say. Poets, artists and playwrights openly contemplated it, examined it, held it up to the light and studied it. Larkin, Samuel Beckett, Dylan Thomas dug it up and replanted it in verse and prose. Damien Hirst is a compelling example of someone for whom death is his muse. Interestingly, late in 2002, the sudden death of his friend, Clash lead singer, Joe Strummer, caused him at the age of 37 to confront his own mortality for the first time.

My childhood

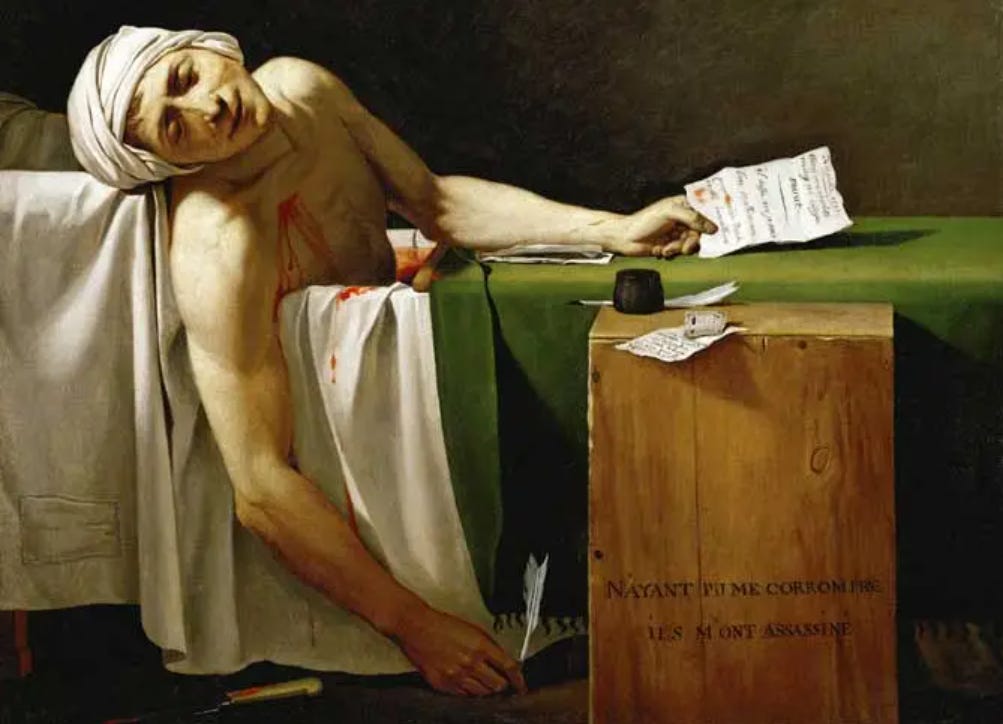

Looking back, death was there, plenty of it too. My parents kept a copy of Der Struwwelpeter (1845) lying about, whose stories absolutely terrified me, such as ‘Pauline, The Very Sad Tale with the Matches’. There were family trips to Madame Tussauds Chamber of Horrors, The London Dungeons, The Tower of London (the torture rack). I’d pour over history books depicting the beheading of King Charles I, the French Revolution guillotine, the murder of Jean-Paul Marat, heads on spikes along Tower Bridge. My younger brother was briefly obsessed with Anne Boleyn (her supposed headless ghost that they say haunts Hampton Court). Three school peers died in tragic circumstances one in an utterly ghastly combine harvester accident while baling hay alongside his dad. As an 8-year-old classmate of his, this news rocked the foundations of my world.

The death of Jean-Paul Marat (1793)

At junior school in Oxford, occasional weekend forays into the town saw us head for the Pitt Rivers Museum where we’d eyeball the gruesome ‘Shuar Tsantsas’ Ecuadorian shrunken heads (no longer on display), their tennis ball sized heads, sown-up mouths (like they’d been prevented from screaming), vacant eye sockets (think Sir Lenny Henry’s masterful cameo as Dre Head on the Knight Bus in the 2004 film ‘Harry Potter and Prisoner of Azkaban’) exerted a macabre pull.

Tsantsas shrunken heads (photo: Hugh Warwick)

Teen goth years

Death slunk away during adolescence, though it lurked like a faint watermark on a printed page, reappearing in my GCSE and A Level English Literature set texts.

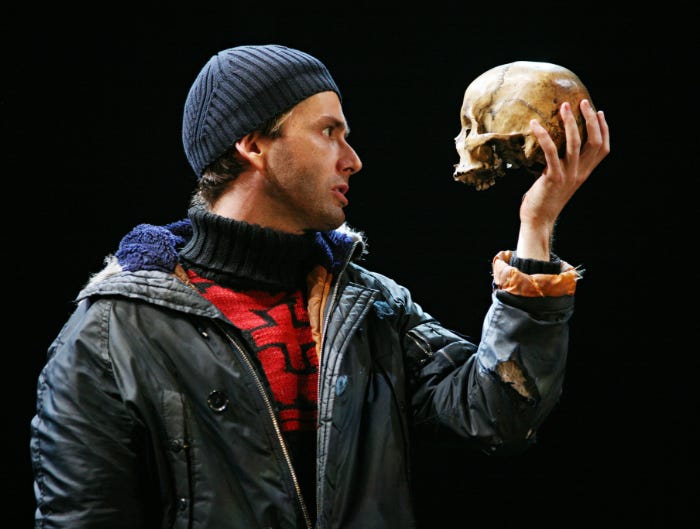

Shakespeare’s Macbeth on learning of his wife’s death says, ‘Out, out, brief candle! Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player. That struts and frets his hour upon the stage. And then is heard no more. It is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.’ (Act V, Scene 5). But it was while studying Hamlet at A Level that death’s certainty really stung. Hamlet’s ‘To be, or not, to be’ soliloquy made me consider whether anything lies beyond this life, ‘but that the dread of something after death, the undiscovere’d country, from whose bourn no traveller returns, puzzles the will,’ (Act III, Scene 1). No one has come back from the ‘other side’ to enlighten us, just radio silence.

As an angry, nihilist goth, drinking black coffee and smoking Camel non-filter cigarettes, Andrew Eldritch’s Sisters of Mercy track ‘Temple of Love’ played loud through my open study door, ‘Life is short and love is always over in the morning’, it hollered. Live fast, die young (went the prevailing teen mantra). Armed with seemingly concrete answers, a lingering uncertainty about death slowly eroded their foundations. ‘And yet to me, what is this quintessence of dust?’ (Act II, Scene 2), says Hamlet contemplating the gravediggers tossing Yorick’s skull back and forth to one another, ‘Imperious Caesar, dead and turn’d to clay, might stop a hole to keep the wind away,’ (Act 5, Scene 1). Its author giving death the right to reply. I too was in its grips.

David Tennant as Hamlet (photo: Ellie Kurttz © RSC)

In 1991, a chill gust of death blew keenly when my wonderful late uncle Pete died a year after I’d gone up to University College London (UCL) to study Latin & Greek. A sparkling senior research fellow of Zoology at Jesus College, Oxford, cancer took him. If not resting on my shoulder, aged 19, death held an outstretched hand forcing me to confront my own mortality. As it was, I was all at sea in London, trying to tough it out in the 15th largest metropolis on the planet. I was lodging in truly bleak accommodation in a house (think Withnail & I) off the Finchley Road, near Hampstead. Keats’ Sonnets had also been a GCSE set text, his ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ was seared in my mind, as achingly sad as it was entrancing. Keats wrote it in 1819 when, unbeknownst to him, he’d likely contracted tuberculosis while nursing his dying brother Tom. The bird’s song prompted him to write in the sixth stanza ‘To thy high requiem become a sod. Thou was’t not born for death, immortal Bird!’ pines Keats. I visited the poet’s Hampstead house; his death mask hung on his bedroom wall. Next, I discovered that the skeleton of UCL’s founder, Jeremy Bentham, was preserved inside a wax effigy of his body in a cabinet on campus, his desiccated head (now separately displayed) lying between its feet. The mummified head frequently toured parts the capital part of pranks by various sports team, sometimes riding a Tube carriage, once allegedly sitting atop of a plumped-out raincoat at a table in a dimly lit corner of a local pub). Death was giving me the run around.

Jeremy Bentham’s wax effigy (photo: courtesy of UCL)

The young adult

I will admit during a torrid undergraduate experience spending way more time outside UCL’s lecture halls than in them. It was the early ‘90’s and Damien Hirst was garnering headlines as an artist who majored on death; blinged-up memento mori. His iconic Tate Britain shark installation entitled ‘The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living’ saw the mammal preserved in a tank of formalin. Some of his other works, ‘With Death Head’, ‘Thousand Years’ (a putrefying cow’s head in which eggs develop into maggots, then flies, only to be zapped by an insect-o-cutor), more recently ‘Exquisite Pain’ (a statue of the flayed martyr St Bartholomew) and ‘Fear of Death’ (a skull made of flies) divided critics and public alike. I loved them, still do. A year later, voting with my feet during a whole teaching term on Caesar’s Gallic Wars (endlessly dreary descriptions of tactical battle formations), I visited Tate Britain again, this time to see Bill Viola’s mesmerising half-hour ‘Nantes Triptych’, an audio-visual installation which showed a woman giving birth (left screen), a mysterious male figure floating in water (centre) and the artist’s own mother on her deathbed (right). A scream, silence… then death’s rattle. These were profound existential questions writ large. I’d purchase student standby tickets to watch Jacobean revenge tragedies at The Barbican. The plays were bloodbaths, stages soaked in gory revenge. I couldn’t keep up with the body count. Death had a front row seat.

‘Nantes Triptych, 1992’ audio-visual installation Bill Viola (photo: Benny Chan)

One snowy winter’s day in 1992, I set out on a four-mile pilgrimage from Kentish Town to London Bridge to seek somewhere to pray. I’d spent my last few pennies on two packs of custard creams. In Southwark Cathedral’s welcoming sanctuary, I found balm for my troubles. I spotted a marble memorial plaque whose bones were so startlingly lifelike I remember reaching out and touching them. Death was ‘speaking’ to me beyond the grave. I started noticing graffitied comments carved into surfaces in UCL’s library, St Paul’s Cathedral and The Monument, inscribed by people intent on leaving behind something permanent of their impermanence. A fleeting ‘I was here’, ‘is my life significant?’. The psalmist in the Bible writes, ‘For like the grass they will soon wither.’ (Psalm 37:2). In between studying, socialising and playing university sport, I would returning to my room to gloomily listen to Richard Burton reciting John Donne’s ‘A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning’. ‘As virtuous men pass mildly away, and whisper to their souls to go,’ his resonant Welsh lilt filling my headphones. I devoured Descartes, Kierkegaard, Nietzsche and Pascal’s ‘Pensées’ (containing his famous “Wager” argument). I re-visited Samuel Beckett’s plays hunting for clues. I read Viktor Frankl’s masterpiece, ‘Man’s Search For Meaning’, in which he identifies why it was some concentration camp victims survived. In 1993, Spielberg’s ‘Schindler’s List’ in which death did not steal the last march. I threw myself into reading World War I British poets. Why? Because death seemed the other side of my bedsit wall.

Shortly after graduating from UCL in 1994, Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain ended his life (by shotgun), which triggered music journos and fans alike frenziedly ferreting through his lyrics looking for clues that might foreshadow his suicide.

In 2016, as a dad on the cusp of middle age, Bowie, Prince and George Michael all died; death jockeying for pole position in the charts. Now in my sixth decade, approaching the ‘fifth’ Age of Man, the seventh seems not far distant now, ‘Last scene of all, that ends this strange eventful history, is second childishness and mere oblivion, sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.’ More recently, I recall listening to Eva Cassidy’s ‘Songbird’ album for the first time, wondering why her life had to end aged thirty-three, questioning why if the Almighty existed, he had yet to bring about brutish ends to tyrants and terrorists across the globe

Onwards towards…

Death for the most part occupies a shadow in the margins of our lives. A loved one is there one minute then gone the next. A pet dies. The death of a work colleague is announced by email. Paul writes in his letter to the Corinthians, ‘O death, where is thy sting? O grave, where is thy victory?’. Put to music by Handel in his ‘Messiah’, it takes on a mocking tilt- cocking a snook, thumbing its nose at death, our ultimate enemy. The froth of life cannot drown out our common fate. Death reigns undefeated. It’s there watching on. At its end, my body, brain, vital organs will all go up in smoke or slowly putrefy into the soil, nutrifying the earth, nurturing plants that will feed animals. From dust to dust. These are merely stark facts, not morbid self-indulgence.

We tiptoe around death, using phrases such as ‘passed away’ or ‘departed’ (like a connecting train someone failed to catch) or ‘croaked’ or ‘popped their clogs’ (my favourite). We try desperately to cheapen its finality. I may briefly be remembered at a funeral or in an obituary (that’s probably pushing it), in photos, a voice recording or a digital avatar, even a Grok-AI robot sashaying down the crematorium aisle singing ‘Bring me sunshine!’ I’ll soon be forgotten and life, in all its colour and glory, will backfill. I noted Bryan Johnson’s Instagram account today, an American entrepreneur hellbent on reversing his biological age, a 47-year-old claiming to be 42. ‘We may be the first generation who won’t die’, he declares. Note, ‘may’, not ‘will’.

I make no bones (sorry) about stating the fact that death has transformed me: from nihilist, to agnostic, sceptic, seeker and Christian. And for that, death needs a thank you handshake. I mention this because it is undeniably significant. I found I couldn’t move beyond the cross, Christ’s cross. I could only look up, transfixed. There he was pinned to it, looking down. The Bible says things like ‘he died and rose again’. Yeah, right, I told myself …and I’ve been shortlisted to be the next Pope! I felt I had to be honest with myself because I figured that the Bible pivoted on the execution, death and purported resurrection of Jesus. Therefore, it posed three questions that, try as hard as I might, I couldn’t dismiss. Its claim is as utterly outrageous as it sounds, borderline preposterous. There’s nothing like it in history, period. It hit hard. By the way, this is not a Christian apology on the sly. I did not go looking for God. This singular event - the resurrection - defies all known, observable laws of physics, chemistry, biology… yada yada yada.

So what? Indeed, so what? You see? It’s very hard to move past it without going, ‘I’m sorry, you what?!’ In other words, do the Gospel accounts amount to wishful thinking, wide-of-the-mark exaggerations? The type of self-aggrandising guff enshrined in local folklore, the pub bore ‘I met this bloke the other day said his mate caught a fish this big’ boast? Did it speak of a delusional minor cult, an extraordinarily effective viral hoax? This would render it ‘malign’, thereby reducing God to a giant clumsy fraud – a ridiculous, self-serving, lying tyrant over whose son countless people have either been martyred, sacrificed all their worldly goods or nailed their living hope on. Or could the accounts allude to someone suffering with a form of personality disorder, somewhat akin to malignant narcissism, undiagnosed, untreated; an upstart firebrand heard god ‘in his ear’ and became the catalyst for a group deluded fanatics? Either way, the Christian God would therefore be an utter sham, the basis of a religious faith that has hoodwinked billions of followers; a tinpot god presiding over a mass ‘Hunger Games’ social experiment.

Jesus didn’t cheat death. He was tortured, crucified and slowly died, so Christianity’s holy text invites us to believe. Because, you see, if this is a lie or in any way inaccurate, then God is an unwholesome fraud, serial abuser and liar. Easter goes down the plughole, Christmas too, the years 1AD and 1BC and all that precedes and follows them also go up in a puff of smoke. A living faith upon which the foundational principles of Western civilisation, culture, laws, ethics, art, literature, architecture, philosophy, social welfare, science, politics, education, music, restorative justice and human rights (besides the obligations of the Ten Commandments) would similarly vanish into thin air, and rightly so. Gone. Forever. Dead.

Can God lie? No, absolutely 100% not. Else, he would be no God worth worshipping at all. He would be insufferably, shabbily evil. Right? Right. So, death, our fiercest of enemies, is the end, right? Yes and no: physically it is, spiritually, not so. The Almighty declared it as such. Maybe, this has provoked you, as Jesus does me, constantly. So, I’ll leave it there.

The End

(or is it?)

Postscript: Today in the Brunet Garden in Oxford, overlooked by student halls of residence, you will see and hear flies toing and froing. You will also see bees from the neighbouring hives, even in Winter, buzzing about the crocuses, in and out of the snowdrops drinking nectar, doing what they do best and pollinating the surrounding ecosystem while oaks and sycamores watch over. You might even say, out of my uncle’s death, there springs every sign of life.